I was not a normal child. At age 2, my favorite pastime was disassembling every child safety device my parents bought. By age 4, I had become an avid user of the original Macintosh (despite being unable to read.) When I hit school, I was… ”impatient” with the pace of the curriculum. Luckily, I had great parents. They were interested enough to provide me with an endless supply of books and extracurricular excursions. They were savvy enough to maneuver me into an excellent charter middle school. And they were affluent enough to send me to a private high school where the teachers stuffed me with knowledge instead of letting the students stuff me into lockers.

Not all children are so lucky. I’m no social scientist, nor am I particularly well informed about the particulars of the American public educational system. What I am is strongly convinced that educational opportunities make an exceptional difference in the life of a gifted child. And that every gifted child in America – irrespective of background – deserves at least the same opportunities I had.

Last week, I read an article in the New York Times about the continued under-availability of gifted and talented (G&T) education, especially to minority students. In our era of unbelievably insane and misguided budget madness, education is something of an easy target. Children, of course, don’t vote. And G&T education is often seen as a luxury which can be cut or as a competitor for a fixed number of education dollars (especially against programs like special education.)

So, naturally, while falling asleep last night I decided to estimate the actual cost vs. benefit of gifted education. The results were somewhat surprising, so I’d like to share them with you.

In short, the conclusion is that it literally costs the government $0 to spend up to $6,500 extra per pupil per year on gifted education. That’s approximately 50% more than the U.S.A. currently spends on the average pupil.

That sounds like a lot, right? Here’s how I got there:

First, we need a few simplifying assumptions:[1]

· Students can be ranked into deciles by academic aptitude [2]

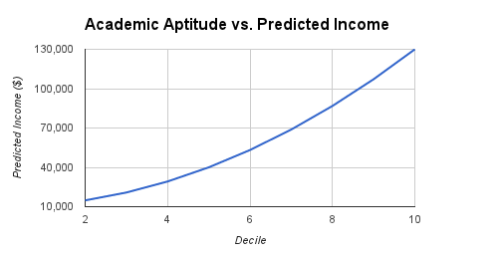

· Annual income is related to academic aptitude by a power law distribution [3]

· A well-targeted education program can raise the average annual income of a decile by 5% [4]

From there, the logic is simple. The annual median income for men in the USA is ~$45k [5]. We assume that the least a worker in the USA can make in a year is $10k [6]. We then roughly fit a power law distribution using income data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau (which has a pretty clear power law shape.)

(source)

This lets us predict annual income by academic decile:

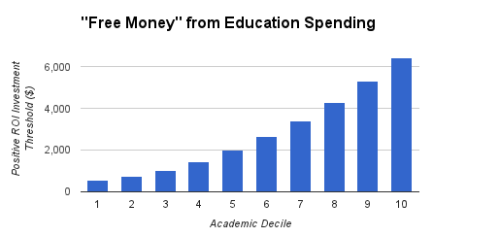

From there, we can predict lifetime income by simply multiplying annual income by the average number of working years (assumed to be 43)[7]. We then multiply lifetime income by our education “bonus” multiplier (5%) to get the additional income each student is expected to generate over her lifetime. We then assume that the government will take back 30% of that extra income through taxes. We divide those collections by the number of years a student spends in school (13), and we have our annualized “free money” threshold, i.e. an amount of spending per pupil that will generate a positive return on investment for the government.[8]

This chart shows the conclusion:

If you’d like to see the calculations step-by-step or you’d like to adjust my assumptions, take a look at this Google doc.

What does this chart say, exactly? It says that if the government spends an additional $5,000 per year on a gifted student, it can expect to collect more back in income taxes over her life than it spent on her gifted education. In other words, up to a point (i.e. $6,500) spending on gifted education is literally free for the government.

That means that any debate about prioritizing gifted vs. special needs education is deeply misguided. It’s not an either/or question. The only reasonable course of action is to just spend the money on gifted education and make all other education spending decisions independently. The government need not even raise taxes to fund the programs; they could issue a 30-year municipal bond and expect to be able to pay back the interest with the extra taxes they collect.

Now this analysis is obviously an oversimplification. Everyone knows that being smart per se does not guarantee a high income.[9] It’s crude at best to assume a static and binary 5% boost in income from simply having a gifted program. And this analysis completely ignores the many social benefits of having better prepared doctors and scientists[10]. I discuss a number of other specific flaws in the footnotes.

Nevertheless, I think the conclusion is sound. Opportunities for accelerated education made a huge difference in my life, and it’s a tragedy that talented students continue to be denied those opportunities just because of their parents’ income. Whether the USA recognizes that fact, China and India certainly will.

Notes:

[1] Relevant data was hard to find on a cursory Google search. If you have better data or feel like making more sophisticated models, please post in the comments!

[2] The idea of innate academic aptitude is controversial enough even without specifying a yardstick. So choose your own! The method of measurement doesn’t affect the logic as long as a measurement can be made.

[3] It’s pretty clear that income itself follows a power law distribution. I’ve never seen a good study about how well academic aptitude predicts income, but to whatever extent America actually is a meritocracy: it will. For every maxim about “A students work for C students”, I’ve met very few unintelligent people who’ve earned large amounts of money.

[4] I pulled this number out of a hat. Intuitively and based on my own experience, I suspect it’s significantly higher. But I wanted to be conservative for the analysis.

[5] The median income for women is substantially lower, but I’m assuming that’s because homemakers are counted. Assuming men and women have equal earning potential if they actually do work, using male income shouldn’t affect the conclusion.

[6] A bit less than full-time minimum wage income, since unemployment rates are much higher for the less educated. http://poverty.ucdavis.edu/faq/what-are-annual-earnings-full-time-minimum-wage-worker

[7] Working from 22-65

[8] I’m ignoring any time-value-of-money issues, both because that would be complicated and because I figure that wages should grow approximately at the interest rate, so discounting vs. wage inflation should cancel out.

[9] In an era where a good data scientist can earn $300,000…we’re getting close. Many top decile people will chose lower income careers, but they will have had at least the option to earn more if they chose.

[10] Medical, technological, and scientific discovery probably also follow a power law distribution. So we should expect that giving our brightest scientists more education will significantly increase the rate of discovery.